Matt Glassman at his Five Points newsletter points out that there are different forms of divided government, where the House, the Senate, or both chambers belong to a different party from the president.

Traditionally, same-party control of both chambers of Congress is a much more common variety of divided government. Of the 21 federal elections that produced divided government since 1933, 15 of them featured the dynamic of the Clinton-Gingrich years: one party-controlling both chambers of Congress and the other party controlling the presidency.The other six included five where the president’s party controlled the Senate but not the House (Reagan’s first three Congresses and the two Obama Congresses after the 2010 Tea Party election) and just one where the president’s party controlled the House but not the Senate (the 2000 election, after Jeffords switched parties).

Are there meaningful distinctions between these various forms of divided government? Absolutely. While divided government in America inherently pits Republicans vs. Democrats, there are both structural features built into the legislative process and political dynamics operating in the public sphere that make unified congressional control different than one-chamber congressional control. The most obvious of these is the direct constitutional link between the presidency and the Senate: nominations. As the constitution provides no formal role for the House in the confirmation of judges and executive branch officials, control of the House alone does not actually create divided government in regard to the nomination process (or the treaty process). Particularly now that the filibuster has been eliminated on all nominations, GOP control of the Senate implies that the record-setting pace of judicial nominations under president Trump will continue in the 116th Congress.

A more subtle distinction is the location and control of political conflict.When one party controls both chambers, there’s a stronger possibility of legislation emerging from Congress that the president feels the need to veto. Indeed, of the twelve vetoes President Obama issued, ten of them came in the final Congress of presidency, when the GOP controlled both the House and the Senate. During the two Congresses in which the GOP controlled only the House, Obama didn’t veto a single bill. His other two vetoes came in his first Congress, when the Democrats had unified control.

Lydia Saad at Gallup:

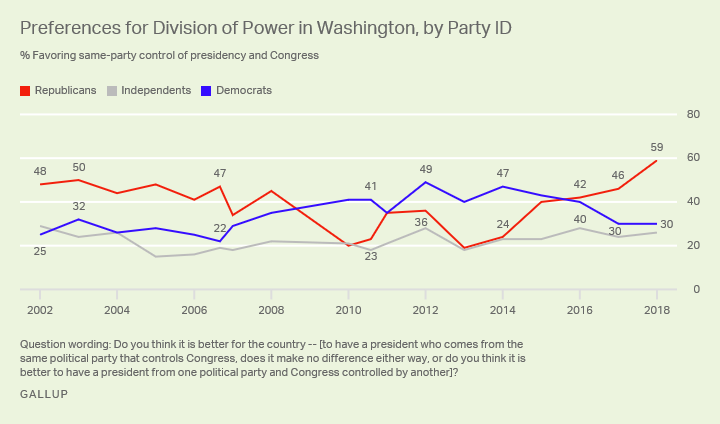

A record-high 59% of Republicans say it is better for the president and majority power in Congress to be from the same political party than for Congress to be controlled by a party different from the president's. That is the highest percentage of Republicans or Democrats favoring one-party control of the federal government in Gallup's trend since 2002. The prior highs saying this were 50% of Republicans in 2003 and 49% of Democrats in 2012.

The trend makes it clear that members of the president's party are almost always more likely than the opposing party to say it's better to have the same party controlling the White House and Congress.

This finding illustrates

Miles' Law:

where you stand depends on

where you sit.